In a move that has sparked a major debate in India’s tech ecosystem, Apple has reportedly refused to comply with the Indian government’s directive requiring all smartphone makers to preload a state-run cybersecurity app, Sanchar Saathi, on new devices. The order also seeks to push the app to existing devices and prevent users from disabling it — a demand Apple is not willing to accept due to privacy and security concerns.

Apple Says “No” — Quietly, But Firmly

According to a Reuters report, Apple plans to formally communicate to the government that it does not preload third-party or government-mandated apps on its devices. The company argues that doing so compromises user privacy, weakens system security, and sets a harmful precedent.

However, Apple is choosing not to escalate the matter publicly or legally — reflecting the strategic importance of India as a growing hardware market.

Apple currently has about 9% market share in India, far behind Android manufacturers like Vivo, Oppo, and Samsung — all of whom have also been directed to install the app.

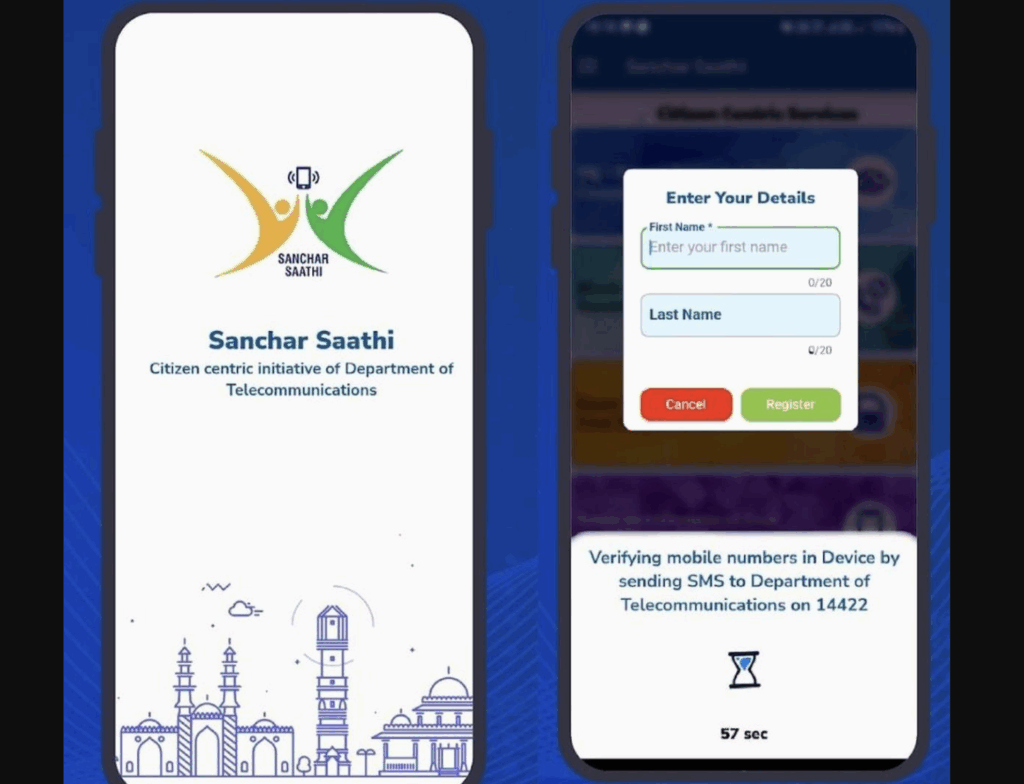

What Is Sanchar Saathi — And Why Is It Controversial?

Sanchar Saathi (meaning Communication Partner) is a government-developed mobile safety app used to:

- Track and block stolen or lost phones using IMEI

- Check the validity of a device

- Identify all mobile numbers registered under a person

- Report suspected fraud communication

The app is already available on the App Store and Play Store. The new mandate, however, goes much further — requiring:

- Mandatory pre-installation on all new phones

- Forced software updates adding the app to existing devices

- A ban on disabling or removing it

Cybersecurity experts warn that an undeletable government app could become a tool for surveillance, data access, or backdoor monitoring — even if unintended.

Government Says “Optional” — But the Order Says Otherwise

Communications Minister Jyotiraditya Scindia said on Tuesday that “the app is optional — users can delete it.”

But this statement directly contradicts the reported contents of the government’s own order, which explicitly states the app must not be removable.

This contradiction has intensified criticism from digital rights groups, who argue that the directive violates privacy rights and undermines user control over devices.

What Happens Next?

Apple is expected to formally convey its objections soon. The government may revise the order or offer clarifications, especially as the pushback grows.

For now, India’s attempt to improve telecom security has collided with global standards of digital privacy — setting up a crucial debate on the future of device governance in the country.